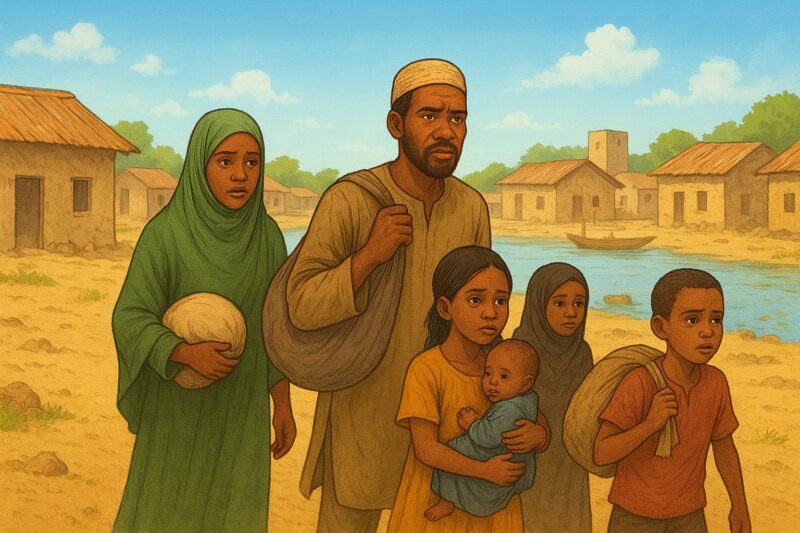

Eight months after the Borno State government completed the relocation of more than 7,790 Nigerians from the Republic of Chad to Doron Baga, their ancestral fishing community in Kukawa Local Government Area of Borno State in northeastern Nigeria, residents say insecurity remains a major concern.

The return was part of a wider effort to resettle thousands of displaced people across Borno State, where improved security has allowed some communities to return home. However, an estimated 1.3 million displaced persons remained internally displaced in the state.

A Fragile Peace Bought with Fear

Although insurgent attacks have reportedly reduced in recent months, the fragile calm in Doron Baga follows an unofficial arrangement between residents and insurgents, under which locals pay taxes to the insurgents in exchange for safety.

One of the returnees, Hassan Sani Said that life has become “a little easier” but at a high cost.

“Months back, the insurgents attacked people frequently when they went fishing,” he said. “Now, they have reached a consensus with residents, especially those engaged in fishing. As one who fishes, you are either given a slip or required to pay 30,000 naira every month, or you pay based on how many bowls of fish you catch.”

According to him, insurgents have stationed themselves at checkpoints near the fishing areas.

“If you have two or three bowls of fish, they calculate it as two bowls, and for each bowl you pay 10,000 naira. That is how you are allowed to go without being attacked,” he explained.

Experts note that this kind of economic control reflects a wider pattern across the Lake Chad Basin region including Kukawa Local Government Area where extremist groups impose levies and taxation on local communities to dominate trade, fishing and agriculture.

Life Between Soldiers and Insurgents

Hassan also described how close the insurgents operate to Nigerian troops, claiming their locations are separated by only a few minutes’ walk.

“When we return from fishing, soldiers sometimes ask if we met Boko Haram members. Even when we say yes, nothing is done about it,” he said.

He also spoke about the difficult situation of those still living in refugee camps in Chad.

“Their stay there is challenging. There is no intervention or support. Some return to Nigeria while others remain in Chad,” he added.

Doron Baga itself bears scars of past violence. In January 2015, satellite imagery and human rights investigations by Amnesty International show that more than 3,100 structures in the community were damaged or destroyed during a five-day assault by the insurgent group.

Expert Reaction

Reacting to the situation, Shettima Mamman, a lecturer with the Department of Criminology and Security Studies at Mohammed Goni College of Legal and Islamic Studies in Maiduguri, said the development raises serious security and governance concerns.

“Resettling people in their ancestral homes is a positive step, but ensuring their safety afterwards is even more important,” he said. “The issue is not the resettlement itself but the security of those resettled.”

He noted that while governments legally impose taxes on citizens, the kind of levies collected by insurgents show that they are acting as a government of their own.

“This is very disturbing, and from a legal perspective, it is completely illegal,” Mamman said. “Residents relying on such arrangements for peace will not last long. What is needed is genuine and sustained security.”

Calls for Stronger Security

Mamman emphasized that the government must strengthen security measures around resettled communities to prevent insurgent control and protect residents from psychological trauma.

“Soldiers and local security outfits should closely monitor what happens in these areas. If they are not well-equipped or properly supported, these lapses will continue,” he warned.

“People in Doron Baga live in constant anxiety,” he added. “If they go fishing and fail to meet the insurgents’ demands, they fear punishment. This uncertainty can lead to serious psychological and health problems.”

Way forward

While the Borno State government continues its efforts to return displaced persons to their ancestral homes, the experience of Doron Baga shows that resettlement alone is not enough. Without effective security, access to livelihoods, and stronger state presence, many returnees remain vulnerable to the same conditions that once drove them from their homes.

Across Borno and the wider northeast, more than 1.6 million people remain displaced, with about 83.5 percent of them within the state.

Until lasting safety and governance are restored, residents like those in Doron Baga will continue to navigate life under a fragile peace bought through fear.

Rukaiya Ahmed Alibe