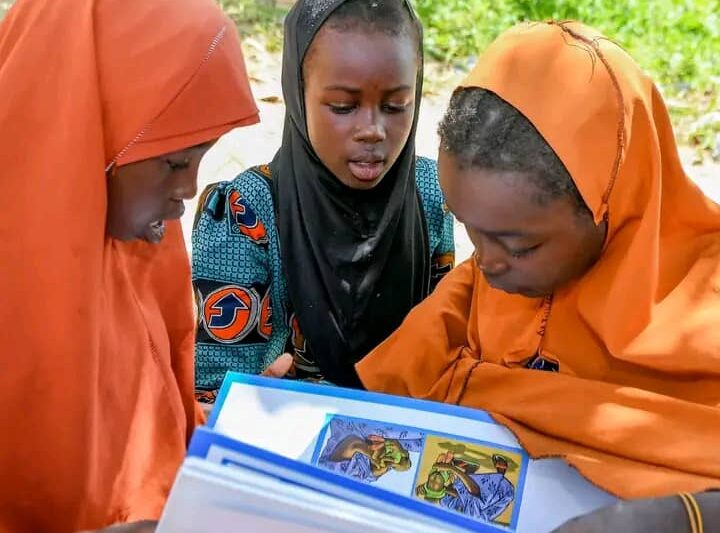

The children of Borno are ‘among the most conflict-affected and educationally disadvantaged in the world’ – and 60% of the 700,000 out-of-school children in the state are girls.

Of the estimated 700,000 out-of-school children in Borno State, 60% are girls – and, unless something is done to redress this urgently, their future looks rather bleak.

Education for girls in Nigeria’s northeast has not been a priority. For generations the role for girls has been domestic – the emphasis has been on marriage, in some cases as early as 11 or 12, and household responsibilities.

A commonly held belief is that girls belong at home to learn and carry out domestic responsibilities.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) says the children of Borno, the epicentre of the “Boko Haram insurgency”, are “among the most conflict-affected and educationally disadvantaged in the world”.

Activist speaks out

Hajja Gana Suleiman, an activist in Borno State, said: “The insurgency and poverty have contributed to the number of out-of-school children, particularly girls.

“Thousands of schools were burnt down during the 16-year insurgency. School teachers were attacked and many were killed. Students – male and female – were abducted.

“The most infamous of these was the abduction of 276 girls from a secondary school in Chibok in 2014. About 90 of the girls – now young women – are still missing. Amnesty International has reported that some of the girls were forced to marry and live with their abductors.”

Suleiman said millions of people in Borno State had been displaced by the insurgency.

“Repeated deadly attacks – particularly at the peak of the insurgency – resulted in the displacement of millions, many of whom still live in abject poverty. Most of these people cannot afford to enrol their children or wards in school. And, if they can, the boy child is more likely to go to school than the girl child.

“Now that relative peace has been restored, the Borno State government is trying to rebuild destroyed schools. It is also doing its best to encourage parents and guardians to enrol their children in schools. But it still needs to do more to support girl child education across the state,” said Suleiman.

Empowering girls

“One of the most significant tools to empower girls within their family and community is education, which is is recognised as a fundamental human right. Gender inequality in education however remains a huge concern, particularly in northern Nigeria.”

Suleiman said some of the barriers that keep girls from getting an education include child marriage, sexual violence, the patriarchal system and traditional preferences.

“The government needs create awareness among parents, especially those in rural communities, about the need for girls to get an education.

“Parents should also know the danger of early marriage – some girls are forced to marry when they are as young as 11 or 12.

“In poor households, girls are often forced into child labour, such as hawking on the streets. Others are sent out to beg for food and money.

“If they do go to school, girls often have to walk long distances which puts them at risk of gender-based violence, including sexual harassment, rape and exploitation. Such forms of violence also increase the risk of teenage pregnancy and lead to a further decrease in girls attending school.”

Financial woes

Fatima Mohammed, a parent in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State, said: “The main challenge confronting us as parents in enrolling our children in school is the lack of finances.

“Most less privileged and displaced parents want to their children to go to school but we simply cannot afford it. Apart from school fees, the cost of uniforms and learning materials is exorbitant.”

Why invest in girls’ education?

The 2025 report by the Global Partnership for Education (GPE), says that more than 118 million girls are out of school worldwide and that limited education opportunities for girls amount to about a US$30 trillion loss in lifetime productivity and earnings.

The report, “Why invest in girls’ education?”, noted that girls have the right to quality education and must be able to continue and complete their studies.

“Investing in girls’ education is one of the smartest investments a country can make. It boosts economic growth as every US$1 spent on girls’ rights and education potentially generates a US$2.80 return; it curbs infant mortality and improves child nutrition.

“Just one additional year of schooling can increase a girl’s potential earnings by up to 20%.

“Still, 118.5 million girls remain out of school across the world – a reality we cannot accept that is also costing countries: Limited educational opportunities for girls amount to US$15 to US$30 trillion in lost lifetime productivity and earnings.”

To try to improve girls’ education, the GPE said it was committed to achieving gender equality through education and making use of its Girls’ Education Accelerator programme which is designed to speed up progress for girls in countries where their education lags behind the most.

The Girls’ Education Accelerator offers countries a strong incentive to focus on girls’ education.

So far, the GPE has raised and committed almost US$200 million towards supporting girls in 10 of 30 eligible countries with funds from donors, private foundations and matched funds from GPE.

The World Bank is a major partner and grant agent for the GPE, playing a crucial role in delivering aid and financing education projects in low-income countries.

GPE in Borno State

The GPE has been instrumental in supporting education in Borno State, focusing on improving access to quality education, particularly for vulnerable populations, and strengthening the education system through initiatives such as teacher training and infrastructure development.

Borno State, along with other northeastern states of Nigeria, faces significant challenges in education because of conflict and displacement, leading to a need for targeted interventions.

The GPE works in partnership with governments, civil society organisations and other development partners to implement its programmes, which include rebuilding damaged school infrastructure, equipping classrooms and improving teacher effectiveness.

The GPE’s long-term goal is to ensure that every child receives a quality education.

With a US$100 million grant, the GPE has supported integrated religious schools and trained teachers to ensure more children attend and stay in school, particularly girls who are most at risk of missing out on an education.

The GPE is working with various schools in Borno State, including the Yerwa Government Senior Girls’ Secondary School, Government College Maiduguri, Shehu Sanda Kyarimi Primary School, Shehu Garbai Government Senior Secondary School and Maimusari Government Primary and Secondary School.

SHETTIMA LAWAN MONGUNO