New study examines the role of learning-related grievances in the insurgency and the place education holds in building lasting peace and addressing historic injustices.

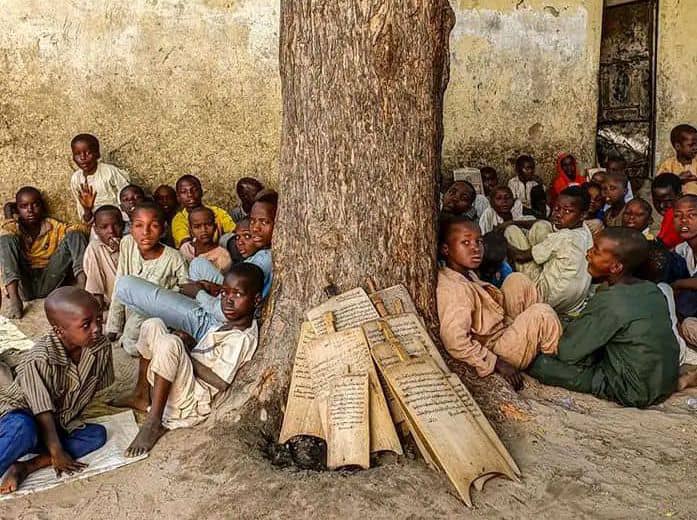

In Borno State – where the insurgency has raged for well over a decade – Islamic schools, known as Sangaya, are often regarded as “breeding grounds for terrorism” where radicalised and disenchanted youths are prime targets for recruitment.

However, little attention has been paid to the ways in which violent conflict affects such schools or their potential to help prevent conflict or contribute to peacebuilding.

The University of Maiduguri – in collaboration with the University of East Anglia and the British Academy – has published a research brief that explores the role disenchantment with secular education has played in the recruitment of members of the Jamā’at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Da’way Wa’l-Jihād (JAS), more commonly referred to as Boko Haram, and the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) insurgent groups in Borno, Yobe and other states in northeastern Nigeria.

The study was led by Professor Yagana Bukar, a senior lecturer and researcher in the Department of Geography at the University of Maiduguri, and Dr Hannah Hoechner, a lecturer in education and international development at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England. They were assisted by Ali Galadima, a lecturer at the University of Maiduguri, and Sadisu Idris Salisu, a community activist and Qur’anic school graduate. The research was funded by the British Academy.

The team of researchers collected data during seven weeks of fieldwork from July to September in 2021. They conducted further research in April this year in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State, and in the Bama Local Government Area, as well as in Buni Yadi, a small town in the Gujba Local Government Area of Yobe State, and in and around Damaturu, its headquarters. These areas have been some of the most heavily affected by the insurgency.

The team conducted 17 interviews and group conversations with former insurgents, 23 interviews and group conversations with Islamic teachers, 10 interviews and group conversations with parents, seven group conversations with Islamic school pupils and 18 key informant interviews.

In an exclusive interview with RNI, Professor Yagana Bukar discussed the findings of the study, titled “Education, Islamic Learning, and northeast Nigeria’s Boko Haram conflict”.

She said the research was structured into six key thematic areas: The issues at stake, Former insurgents’ views on education, Sangaya schools as recruitment grounds, How the conflict affected Sangaya schools, Education for a lasting peace, and Policy recommendations.

Bukar said the research aimed to draw the attention of policymakers to pave a way to address the root causes of the insurgency.

THE ISSUES AT STAKE

Bukar said the “Boko Haram insurgency”, which began in 2009, had ravaged northeastern Nigeria and the neighbouring countries of Chad, the Niger Republic and Cameroon in the Lake Chad Basin.

“Destruction, bloodshed and mass displacement have marked the region for years.”

She said the youthful base of the insurgency, its high-profile attacks on secular schools, as well as the many kidnappings of pupils, had prompted questions about the role of education-related grievances in the conflict, as well as about the place education held in building lasting peace and addressing historic injustices.

“In a global context of widespread fears over Islamic militancy, Islamic schools have often uncritically been declared ‘breeding grounds for terrorism’, with little attention paid to the ways in which violent conflict affects such schools or their potential to help prevent conflict or contribute to peacebuilding.”

The research brief “steps into this gap”, scrutinising the widespread belief that Qur’anic schools (Sangaya) have been prime recruitment grounds for the insurgency.

“While our findings mostly confirmed a large presence of former Qur’anic pupils among the insurgents, we highlighted both the pervasiveness of forced recruitment and the harmful consequences for this education system of generalised suspicion.

“There is a need for more sympathetic approaches, notably in the context of crumbling community support structures which have been worsened by largescale impoverishment and the breakdown of former rural livelihoods, she said.

“Therefore, in a nutshell, we document increased demand for locally provided education that combines secular subjects with a broadened Islamic curriculum and recommend policies to facilitate this.”

FORMER INSURGENTS’ VIEWS ON EDUCATION

Bukar said the research showed that the public and media were strongly focused on insurgents’ apparent hostility towards secular education.

JAS founder Muhammad Yusuf’s preaching against the permissibility of secular education had earned his movement the nickname “Boko Haram” or, as it is loosely translated, “Western education is forbidden”.

High-profile attacks on secular schools, such as the massacre of 59 teenage boys at the Federal Government College in Buni Yadi in the Gujba Local Government Area of Yobe State in February 2014, and mass kidnappings of pupils, including 276 schoolgirls from the Government Girls’ Secondary School in Chibok in Borno State in April 2014, had furthered perceptions of the insurgency being fuelled by opposition to secular or Western education.

“While Muhammad Yusuf’s rejection of secular education resonated with some of our interviewees, opposition to secular education was not discussed as a major factor driving recruitment.

“Our respondents mostly discussed material incentives, perceptions of the insurgents doing ‘God’s work’ [Aikin Allah], the pull of family members and peers, as well as fear of retaliation, as the reasons people joined the insurgency.

“Thus, forced recruitment was another key theme.

“Our respondents’ views of secular education were also shaped by their experience of having been led to believe in an ideology they later discovered to be misguided,” Bukar said.

The respondents told researchers that many graduates of Qur’anic schools struggled to find meaningful employment.

This highlighted the need to avoid future disenchantment, Bukar said.

“Education interventions must pay close attention to whether the skills they impart can indeed be translated into meaningful opportunities.”

SANGAYA SCHOOLS AS RECRUITMENT GROUNDS

“Qur’anic or Sangaya schools, where male pupils – known as almajirai – are sent to live with a teacher – a Malam – to study the Qur’an, mostly depend on charity to meet their daily needs. These schools are often considered key recruitment grounds for the insurgency.

“Our research participants mostly confirmed that Sangaya pupils and teachers made up a significant share of insurgency members. But they emphasised the fact that insurgents recruited members from a range of educational backgrounds, as well as among those without any education.”

Bukar said that going forward, it was important for policymakers to steer clear of simplistic victim-perpetrator dichotomies that risked eroding empathy for one or the other.

“Trust-building exercises between Sangaya school stakeholders and the security forces can help safeguard against abuse of rights in the future.”

HOW THE CONFLICT/INSURGENCY AFFECTED SANGAYA SCHOOLS?

Bukar said historically, many Qur’anic schools were embedded in the rural economy, with farming being a key source of livelihood for teachers and pupils.

With many schools and teachers being displaced from rural areas because of insecurity, these livelihood structures had broken down.

Community support for Sangaya schools had also declined because of mistrust and widespread impoverishment.

“The teachers in our study found it much more difficult now than before to find accommodation and assistance for themselves and their pupils.”

Most parents from communities that had previously relied heavily on the Sangaya education system expressed new reservations, highlighting the risk of children being kidnapped or led astray, or going hungry. They told researchers they preferred to keep them close-by, leading to a decline in “full-time enrichments”.

“Qur’anic teachers in our study confirmed that most of their pupils nowadays are day students living with their parents.”

Bukar said that, for policymakers, this raised the challenge of providing alternative employment opportunities for those with only Qur’anic knowledge who might no longer see a future in teaching Sangaya pupils.

EDUCATION FOR A LASTING PEACE?

“In the aftermath of the conflict, the overwhelming majority of our respondents reported an increased interest in all forms of education or knowledge and argued that it was best for children to receive both religious and secular education.”

Respondents told researchers that both forms of education were “helpful in fostering peace, unity and stability” and were imperative to prevent future conflicts “like the Boko Haram insurgency”.

Education should include “enlightening” young people, making it more difficult for them to be misled in future.

Bukar said it was important to instil discipline and keep young people busy, preventing problematic behaviour, “such as making friends with the wrong people”.

“Many of our respondents consider Islamic education an integral part of ensuring lasting peace and consider sound religious knowledge important for ensuring future resilience against indoctrination.

“Our respondents value secular education for its promise of opening up economic opportunities and facilitating participation in ‘modern life’. They said knowledge of technology would enable people to move elsewhere and mingle with others.”

Several respondents, notably those who had experienced graduate unemployment themselves or in their family, raised concerns over the uncertain payoffs of secular education in terms of actual income opportunities, Bukar said.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

“First, policymakers need to ensure that education provision is genuinely free and sufficient to meet increased demand – and this requires adequate resourcing.

“Second, policymakers need to facilitate young people’s acquisition of both secular and religious knowledge by providing adequate support for institutions offering integrated education [Islamic or Qur’anic schools that include secular subjects] and to facilitate trust and cooperation. The findings show that it is imperative for Islamic schools to retain a say in all decisions concerning them.

“Third, curriculum content needs to address concerns about employability and broad religious learning.

“Fourth, policymakers should facilitate the upskilling and redeployment of Sangaya graduates.

“Finally, activities designed to encourage exchange and understanding between people of different education backgrounds – and between members of different government institutions and Sangaya school stakeholders – can help increase social cohesion, acceptance of secular education, and empathy and respect for almajirai and their teachers.”

SHETTIMA LAWAN MONGUNO