Working in the Sahel region – Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, The Gambia, Guinea, Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Nigeria and Senegal – is becoming increasingly dangerous for journalists, many of whom have been subjected to death threats, assaults, obstructions, the ransacking of equipment and premises, and arrests.

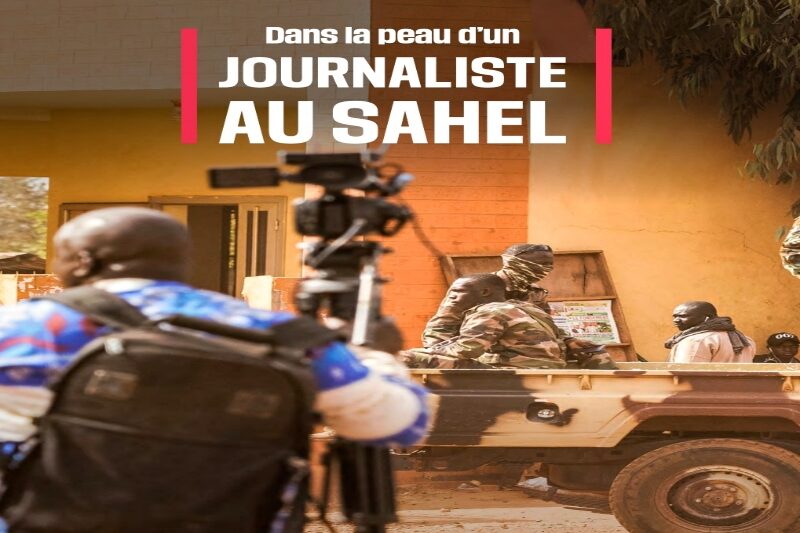

“In the Skin of a Sahel Journalist”, a 21-page report, Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF – Reporters Without Borders) says that, from Chad to Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso, journalists’ working conditions have deteriorated significantly.

It says covering the many crises in the Sahel freely is becoming increasingly difficult, particularly within countries that are under military control.

The Sahelian strip that crosses the continent from west to east is threatened to become “the largest information-free zone in Africa”, the report says.

The pressure exerted by the juntas in power and their patriotic injunctions “favour the development of a journalism under orders and a phenomenon of omerta [code of silence] on certain sensitive subjects,” says Sadibou Marong, director of the RSF’s sub-Saharan Africa office.

Since November 2013, at least seven journalists have been killed in the Sahel. Six are missing. Nearly 120 have been arrested, with some still being held. Death threats, assaults, obstructions and the ransacking of equipment and premises can be counted in dozens.

However, the report also notes new initiatives, such as the Yafa, Kalangou and Tamani Studios which cover news in the different local languages spoken in the Sahel, have provided important information to populations facing crises. The same is true of Radio Ndarason Internationale in the particularly dangerous cross-border area of Lake Chad.

RSF recommends that members of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC) draw up a sub-regional code of conduct for the safety of journalists in conflict zones, particularly with regard to women journalists; recognise and guarantee the right to information as set out in the Partnership for Information and Democracy; and support the development and establishment of a regional media support agency.

The report recommends that international partners in the Sahel countries fund and sponsor training on the safety of journalists and help the media put in place safety protocols.

Local and international press have been facing a “constant deterioration” of their working conditions for the past 10 years, says the report, which covers the working conditions of journalists particularly in Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Chad and also in northern Benin, which faces similar security challenges.

- The Partnership for Information and Democracy is an intergovernmental non-binding agreement endorsed by 50 countries around the world to promote and implement democratic principles in the global information and communication space. It was formally signed during the 74th United Nations General Assembly in September 2019.

Mbodou Hassan Moussa